Crucial battles are currently underway in Iran’s religious and political establishment, away

from the reach of the television cameras, writes Mustafa El-Labbad

——————————————————————————-

The final days of 2009 brought a dramatic shift in Iran’s domestic equation, creating a

situation very different from the one that had prevailed only a few weeks earlier. New sets of

rules have come into play on the Iranian political scene, which has been

transformed into a

three-sided dynamic consisting of grassroots activism, competition in the religious

establishment and the power conflict at the upper echelons of the Iranian state.

As the world followed the scenes of the mass protests that swept Iran’s major cities last year,

media hostile to the Iranian regime proclaimed its immanent fall, while pro-Iranian media

shrugged off the demonstrations as the work of “outlaws” and “agents of the West”. If one side

was vulnerable to an excess of optimism unsustained by realities on the ground, the other was

gripped by a spirit of denial that ignored the political meaning of the demonstrations.

In both cases, prejudice outweighed objectivity and one- dimensional media images overshadowed

details that combine to create a much more complex picture. As the pro- and anti- Ahmadinejad

camps clashed over the import of the scenes taking place in front of the television cameras,

they also lost sight of the other two legs of the Iranian political triangle.

Two other crucial battles are unfolding more subtly, away from the eyes of the cameras, in the

religious and the political establishments. One is the contest over moral and spiritual

authority being waged by Grand Ayatollah Youssef Sanei. The other is the struggle for survival

in the upper echelons of the Iranian political and decision-making structures.

The chief protagonist here is Hashemi Rafsanjani and his success or failure will to a

considerable extent shape the future of domestic power in Iran.

MOUSAVI AT THE CROSSROADS OF AN IMPASSE: Former Iranian prime minister Mir-Hussein Mousavi was

thrust to the fore of the Iranian political stage following the 10th presidential elections.

The official results of these elections, in which Mousavi presented himself as the reformist

candidate, triggered widespread protests among reformists against alleged electoral fraud and

the “forging of the will of the electorate.”

Refusing to cave in to pressure to bow before the official outcome of the polls, Mousavi

succeeded in sustaining his protest against the proclaimed winner, Ahmadinejad, and the

Revolutionary Guards behind him. Over the following months, the Iranian president adamantly

persisted in ignoring the demands of the demonstrators, formed an ideologically uniform hard-

line government and lashed out at the reformists as traitors amidst tightened security

measures.

Up to December last year, the opposition had been reduced to weak and sporadic outbursts.

However, the funeral ceremonies for the late Ayatollah Hussein Ali Muntazari and the

commemoration of Ashura in the same month afforded opportunities to make its presence felt.

The Iranian opposition has various weak points, foremost among them the lack of a charismatic

leader capable of rallying widespread mass support. Mousavi’s popularity pales next to that of

Ayatollah Khomeini, and beyond this there is an organisational problem.

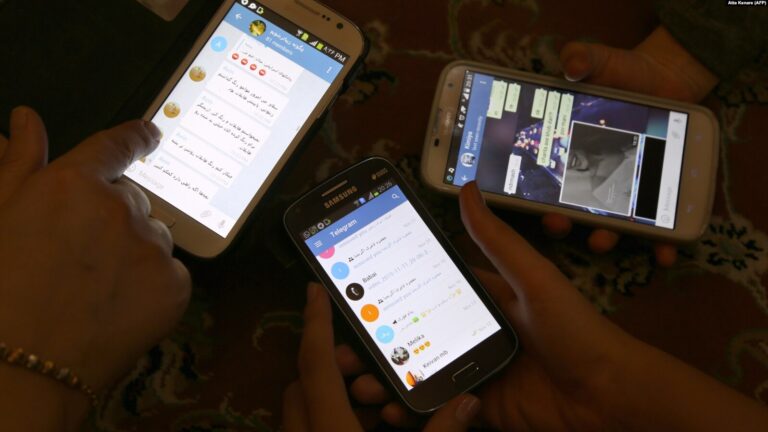

Both the Khomeini and Mousavi opposition movements availed themselves of the technology of the

age — cassette tapes conveyed the exiled Khomeini’s voice and views to the people before 1979,

while the Internet and Facebook were Mousavi’s means of connecting with supporters in 2009.

Mousavi also has had the advantage of modern technology to mobilise demonstrations on days when

mass assemblies are possible in Iran, and these are quite frequent in the autumn and winter.

Demonstrators prepared themselves to take advantage of the ceremonies surrounding Ashura in

December, just as they had geared themselves up for Students’ Day in October and Jerusalem Day

in September. And already the government is taking precautions against opposition rallies

during the week-long commemoration of the Iranian revolution in February. However, it will be

several months before such an official occasion presents itself again, and they will have to

wait until the commemoration of the death of Ayatollah Khomeini himself in June.

This need to rely on state holidays in order to express its demands raises doubts over the

opposition’s ability to sustain its impetus. A third problem is that unlike Khomeini Mousavi is

not leading a revolution and only wants to introduce reforms. Mousavi is not selling an

ideology. Unlike Khomeini, who broadcast his appeals from Paris, Mousavi is in Tehran and

within the reach of the Iranian authorities.

Thus, in addition to its lack of a sufficiently charismatic leadership and its incapacity to

sustain itself organisationally, the opposition also lacks a sufficiently radical agenda, and

its leadership lacks manoeuvrability in pressing for its demands.

However, the climate in Iran today cannot be compared with the massive revolutionary tide that

prevailed in pre-1979 Iran. In his final years, the Shah had lost contact with the Iranian

people, and the welfare and security of the regime rested solely upon a narrow class of

business magnates and an even smaller coterie of senior army officers.

Today, supporters of the Iranian regime number in their millions, whether they are drawn by the

Shia Islamist ideology of the regime, or have vested interests in it as state employees, who in

themselves number in the millions. When the regime’s proficiency in securing the satisfaction

of broad segments of the populace by channeling a significant chunk of the country’s huge oil

revenues into subsidising essential goods is added, the dynamic in Iran today becomes even more

apparent.

This is not a case of a regime that is isolated from its people and faces opponents who have

massive popular support. Rather, it is the case of an opposition drawn from certain strata of

society against a regime that enjoys massive support among other strata of society, and this

poses complications for the opposition’s mission.

Moreover, on top of its millions of supporters, the regime has another important asset to draw

on, which is its military might as embodied in the Republican Guards. That the regime has not

yet had to resort to this army in itself is significant and signifies that its dilemma has not

yet reached the magnitude of an existential crisis.

Today’s Iranian opposition has not been able expand into a broadly-based civil-disobedience

movement or even to attract new segments of society into its ranks. Nevertheless, Mir- Hussein

Mousavi’s five-point initiative issued in the wake of the violent suppression of the latest

round of protests demonstrates an acute awareness of the opposition’s weak points.

In addition to the points above, the opposition also lacks an explicit ideological framework.

Although it largely draws its support from the urban upper-middle classes, it still consists of

a relatively loose mosaic of different age groups and political outlooks. As such, it cannot

afford to hamper itself within an ideological straightjacket, and Mousavi’s initiative has

struck chords that can win the broadest possible unanimity without leading to a splintering of

this mosaic.

Mousavi has therefore insisted that the executive, parliamentary and judicial authorities

should assume responsibility for the suppression of the demonstrations. He has also called upon

the government to ensure free and transparent elections, to free political detainees, to

guarantee the freedom of the press, and to acknowledge the people’s right to freedom of

opinion.

As ideologically broad as these initiatives are, they nevertheless raise the tenor of the

opposition’s challenge. This applies especially to the first demand, which was clearly intended

to sustain the opposition’s impetus, for the three branches of government could not possibly

accept responsibility for the consequences of the violent suppression of the demonstrations

without handing the opposition a clear victory.

Naturally, the prospect of such an eventuality is very weak in the light of the current

domestic balance of power. The other four demands, while popular, offer little that is new or

particularly defiant. Nevertheless, when the former conservative presidential candidate Mohsen

Rizai took this statement as proof that Mousavi did not pose a challenge to the revolutionary

order, the editor-in-chief of the conservative Kayhan newspaper, Hussein Shariatmadari, who is

close to the Office of the Supreme Guide, lashed out vehemently at what he saw as an attempt to

mediate between the protesters and the government.

Although the regime’s rejection of Mousavi’s initiative could have been expected, it is

interesting to contemplate what it might have accomplished had it acted otherwise.

For one thing, if the regime had engaged the opposition in dialogue, even under certain

stipulated conditions, it would probably have succeeded in exposing the contradictions in

interests and outlooks among the diverse groups that make up the opposition camp, while

simultaneously preventing any further deterioration in its image in the region and abroad.

The opposition’s major strengths, therefore, have been its ability to embarrass the regime

abroad and to dent the legitimacy of the Ahmadinejad presidency at home, even if the

demonstrations have done nothing so far to shake the regime’s grip on the key instruments of

power.

More importantly, however, with the end of the era of an establishment that embraced

“conservative” and “reformist” wings and the drawing of the battle lines between “the system”

and “the opposition,” a domestically based opposition movement has become a factor in Iran’s

internal political equation. This is the opposition’s chief accomplishment so far.

GRAND AYATOLLAH YOUSSEF SANIE AND THE RELIGIOUS ESTABLISHMENT: Religion has such a pervasive

influence on politics in modern Iran that it is virtually impossible to separate the two.

This applies not just to the post-revolutionary era, but also to the country’s modern history

throughout the 20th century. So closely are religion and politics intertwined that the balance

within the religious establishment is a prime indicator of the balance within the political

establishment as a whole.

The reform movement found in Grand Ayatollah Hussein Ali Muntazari a unique and powerful

spiritual authority with which they could arm themselves ideologically against the

fundamentalist hard-liners.

Muntazari, who spent 20 years under house arrest from his falling-out with Khomeini in 1989

until his death in 2009, was a vehement opponent of the regime, but his opposition rested on a

theological basis. With his death in December, the reformists lost a major spiritual and

political symbol and felt that they had suffered a moral setback in the face of their

adversaries.

Although the Grand Ayatollah’s son Said Muntazari declared that Mousavi should replace

Ahmadinejad as president in order to restore calm to the country, his support did not furnish

the opposition with the same spiritual and political immunity as his father’s had done earlier.

The opposition therefore turned to Grand Ayatollah Youssef Sanie to fill the gap left by

Muntazari’s death.

Had the latter’s followers transferred their allegiance to Sanei, Sanei would have become one

of the most influential ayatollahs in Iran and elsewhere. In Shia tradition, an ayatollah’s

disciples and followers entrust a fifth of their profits to him for use in religious education

and other religious affairs, and they look to him as their guide and mentor in all matters,

both spiritual and mundane. Upon an ayatollah’s death, this allegiance is transferred to

another religious authority.

Born in 1937 in a village on the outskirts of Isfahan, Grand Ayatollah Youssef Sanei was born

into a family of clerics. His grandfather, Ayatollah Hajj Mulla Youssef, was a devout and

widely respected cleric of his time, who had been tutored in philosophy by the eminent Iranian

philosopher Jahangir Khan and in Islamic jurisprudence by Grand Ayatollah Mirza Habibullah

Rashti.

Sanei’s father, Hujjat Al-Islam Mohamed Ali Sanei, was also a prominent religious scholar, and

his son followed in the family tradition. Following preparatory studies at a seminary in

Isfahan from 1946 to 1951, Sanei transferred to the Qom seminary where he was soon awarded the

title of Thiqat Al-Islam (trustee of Islam). In 1955, he ranked first in the advanced level

examination, for which he was awarded the title Hujjat Al-Islam (expert on Islam) and received

the commendation of Grand Ayatollah Borujerdi, the leading Shia spiritual authority in the

world until 1961.

Sanei continued his studies at the hands of the top Shia theologians of the day, such as Grand

Ayatollahs Borujerdi, Mohaqeq Damad and Araki, as well as with Imam Khomeini. In keeping with

his record of outstanding achievement, he obtained the ijtihad degree, qualifying him as an

ayatollah, at the age of only 23. In 1975, he began his formal career as a lecturer in

divinity, in the course of which he attracted numerous disciples and followers, many of whom

went on to become eminent seminarians and officials in the religious and post- revolutionary

political establishment.

A prolific writer, among Sanei’s most important works are The Disciple’s Beacon, The Essence of

Thoughts, A Selection of Islamic Laws, One Hundred and Ten Questions on the Pilgrimage, and a

ten-volume series on contemporary jurisprudence. In these and other writings, Sanei airs his

progressive views, notably on the equality between men and women and between Muslims and non-

Muslims.

Sanei has also been an active supporter of the reformist trend. Before the presidential

elections in June, Sanei invited the reformist candidate, Mir-Hussein Mousavi, to his home and

honoured him with the praise, “you are the fruit of the life of Imam Khomeini in politics and

the management of the affairs of society.” Mousavi returned this high compliment with the

words, “you are a great spiritual authority, for whom I have always had the deepest affection.”

Sanie became more resolute in his support for Mousavi and the reformists following the death of

Muntazari and the mass turnout for the funeral ceremonies of the late Grand Ayatollah in Qom

and elsewhere, which doubled as an occasion for reformist demonstrations. That Sanie had

decided to fill the vacuum left by Muntazari was evident from the telegram that conveyed his

condolences, which, in the tradition of the Shia religious establishment, carried far broader

political and religious implications.

It is little wonder, therefore, that this telegram should have triggered such a speedy response

from pro-Ahmadinejad supporters within the religious establishment. The Association of

Seminarians at Qom, which is closely connected to the Ahmadinejad camp, issued a statement

declaring that Sanei lacked the qualifications necessary for the post of marja’iya (a spiritual

authority in Shia Islam).

This position was quickly supported in a sermon delivered by the hardline fundamentalist

Ayatollah Ahmed Khatami in Tehran. However, Sanei was not without some prominent supporters of

his own in the religious establishment. The pro-reformist cleric Ayatollah Tahiri, formerly

responsible for delivering the Friday sermon in Isfahan, and the Society of Fighting Clerics,

to which former Iranian president Mohamed Khatami and presidential candidate Karroubi belonged,

upheld Sanei’s credentials.

When asked about the statement by the Association of Seminarians at Qom, Grand Ayatollah

Sistani, residing in Iraq, responded that the association was not an agency that could

designate religious authorities. The response of this eminent Shia figure can also be taken as

an expression of support for Sanei. Grand Ayatollah Makarem Shirazi and Grand Ayatollah Mousavi

Ardibeli were even more explicit, stating that Sanei did indeed possess the necessary

qualifications to serve as marjaa lil- taqlid (an authority to be emulated) and, hence, merited

the title of Grand Ayatollah.

Clearly, the dispute over Sanei’s credentials has thrown into relief a fault line between

Ahmadinejad’s supporters and reformists in the Shiite religious establishment. The former are

led by Ayatollahs Misbah Yazdi and Nouri Hamdani and the latter by Ayatollahs Zanjani Mousavi

and Youssef Sanei. Among the more prominent religious figures to remain on the fence are Grand

Ayatollahs Wasafi Kalbaykani, Wahid Kharasani and Jawadi Ameli.

The rise of Youssef Sanie to the rank of Grand Ayatollah could give the reformist camp a

stronger hand within the religious establishment than it has in the streets. The clerics may

receive only a fifth of believers’ profits to be spent on seminaries and religious affairs,

which is next to nothing compared to the oil revenues at the government’s disposal. However,

their moral and political weight is proportionately much greater than their material weight.

After all, the religious establishment is a fundamental component of the legitimacy of the

Iranian regime and the political balance of the post-revolutionary order, which since its

founding in 1979 has been based on an alliance between the hawza (seminary) and the bazaar.

Only subsequently did the Revolutionary Guards become a third component of the Iranian regime,

and their rise was reflected by the election of Ahmadinejad as president.

RAFSANJANI AND THE UPPER ECHELONS OF GOVERNMENT: Ayatollah Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani is

unanimously regarded as the second most powerful figure in the Iranian regime after the Supreme

Guide. Opinions differ only on the distance that separates him from the number one post.

Rafsanjani has held several senior government positions since the 1979 Revolution. He served as

speaker of parliament and two terms as president between 1989 and 1997. He is currently

chairman of the Council of Experts, which is responsible for selecting, monitoring and

dismissing the Supreme Guide, and chairman of the Expediency Discernment Council, responsible

for resolving conflicts between the country’s various constitutional bodies.

A member of the pioneering generation of the Iranian Revolution, Rafsanjani was always close to

Imam Khomeini. Indeed, such was Khomeini’s trust and confidence in him that he was put in

charge of managing the Iranian war effort during the Iraq-Iran war in the 1980s, even though he

was neither president nor even prime minister at the time.

Following Khomeini’s death, it was Rafsanjani who orchestrated the succession in favour of the

current Supreme Guide over more senior and more scholastically qualified ayatollahs.

The complicated relationship between Rafsanjani and Supreme Guide Ali Khamenei goes back a long

way. Both were close associates of Khomeini, and both were accused by Muntazari of conspiring

to oust him as heir designate to Khomeini two months before the latter’s death. Rafsanjani and

Khamenei attained approximately the same degree of juristic education, both have held key

administrative posts since Khomeini’s death in 1989, and both steered the processes of

reconstruction and rehabilitation of Iran’s regional and international relations following the

Iraq-Iran war.

Yet, Ahmadinejad’s victory over Rafsanjani in the 2005 presidential elections marked a turning

point in this historic relationship. However, like Sisyphus doomed to an eternity to push a

stone uphill only for it to tumble down the other side, Rafsanjani — against the predictions

of many — proceeded with grim determination to push his career out of the abyss until he

attained the centre of the Iranian political fray once again.

While his adversaries see him as a man driven solely by a lust for power and influence on

behalf of his wealthy mercantile family and having tentacles in every corner of the state

apparatus, less hostile observers regard him as an experienced pragmatist who is not only adept

at navigating Iran’s complex political terrain, but also pulls many strings behind the scenes.

Unlike Mousavi, Karroubi or Khatami, Rafsanjani is able to influence the upper echelons of the

Iranian state. Contrary to the reformist trio, Rafsanjani suffered no loss of presence when he

parted ways with the regime. Because of his extensive influence in the establishment, he

continues to have supporters in the ministry of foreign affairs and to carry clout in such

sensitive ministries as the ministries of petroleum and international trade.

Moreover, Rafsanjani is not an electoral or professional phenomenon. Rather, he is a creature

of the Iranian state. Herein resides the quintessential difference between him and the

reformist trio, a difference in part made possible by his extensive vested interests in the

current order.

Contrary to the three reformist leaders, Rafsanjani fully appreciates that president

Ahmadinejad’s strength in the current political equation derives more from the government

forces that back him than from his popular support, real and extensive though this is. Because

of this awareness, Rafsanjani’s desire to see Ahmadinejad removed from power has not blinded

him to the distinction between Ahmadinejad and the system as a whole. He therefore prefers a

surgical approach to the elimination of the incumbent president, and he is known for the skill

with which he can wield the political scalpel without causing dangerous side effects for the

regime.

Yet, Rafsanjani also faces a major problem, which is that Ahmadinejad also represents the

Republican Guards, an institution that has become so tightly interwoven with the weft and warp

of the Iranian state over the past five years as to defy Rafsanjani’s micro-surgical skills.

The task that Rafsanjani has set himself is thus much more complex and delicate, for any

incisions his scalpel makes will immediately reverberate throughout Iranian political alliances

much more profoundly than any demonstrations on the streets.

The modern media can easily capture the din of demonstrations, the clamour of their suppression

and the grimness of their bloody aftermath. However, the fate of the triangle of Iranian

political power will be more heavily contingent upon Rafsanjani’s ability to obstruct the

Ahmadinejad camp and to seize more ground from which to extend his own influence.

Ultimately, Rafsanjani has two avenues open to him. One would be to create a breach between

Supreme Guide Khamenei and the Republican Guards that would give him the opening to cause a

dramatic shift in the current balance of power. The other avenue would be to fail at this and

thus find himself face-to- face with the Supreme Guide and behind him the Republican Guards

more firmly ensconced in power than ever. However, the overall power balance in Iran will be

determined by the sum total of scores in each of the three battles in the triangle of Iranian

domestic power.

Because of the dialectical relationship between domestic and external politics, foreign

+ There are no comments

Add yours